Every era of British history has its own personality. The Romans? They're the makers of our laws and language, along with just about everything else. The Normans? We have William the Conqueror, the Domesday Book, and the Battle of Hastings. The Tudors? Henry VIII racking up more wives than Norman Mailer.

As for the Edwardians... hmm, that's the problem with Edwardians. They're a blip. Ask people to describe what happened at the start of the 20th century and they'll say, "Er... Queen Victoria died?" and then, "the First World War?" and if you're lucky, "the Titanic?". That's a gap of almost 15 years where, in our public consciousness, nothing happened.

It's a problem I encountered when deciding to write my first adult murder mystery. I'd spent 15 years writing books for children: after a decade and a half spent creating stories about loyal dogs (I am Rebel ) and valiant knights (Small Wonder), I was quite looking forward to slaughtering someone in graphic detail. If I had any time left over, I could try writing a terrible sex scene too.

All I needed was a hook - something unique to hang the plot from. I've always been drawn to unusual, lesser-known moments of history, and I found the perfect example in the Halley's Comet Panic of 1910.

For a few months, people believed that Halley's Comet was going to flood the atmosphere with poisonous gases when it passed Earth, killing all life on the planet. My wife's grandfather - who lived in a small farming village in Lesbos - even remembered the villagers discussing whether they should stand on the nearby hill and hope that the poisonous gases settled at ground level. The more I learned about the Panic, the more incredible it sounded. There were riots! Stampedes! People built comet shelters and bought anti-comet umbrellas! They took out comet insurance (not including death by fright)! It was so bizarre and outlandish, it felt like you couldn't make it up: in short, it was perfect.

In my book, I decided that a foolish Viscount would seal up his mansion to make it impervious from poisonous gases. He would lock every door, bolt every window, block every chimney, shut away every member of the household into their own separate rooms to survive the apocalypse... but come the morning, the only victim is him, found slaughtered with his family crossbow in a locked study - which, naturally, no one entered or left.

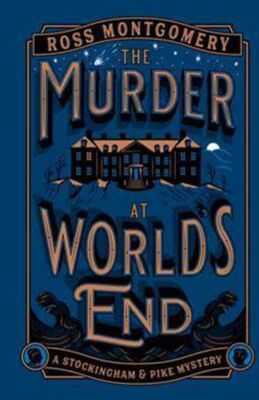

The rest of the book followed from there: I love unlikely detective duos, so I teamed a hapless young under-butler with a shady past with the Viscount's erratic elderly aunt - a secret genius with a foul mouth, who's kept locked up in a corner of the mansion for her own safety (and everyone else's). I had my hook, my mystery, my setting, and my detectives - The Murder at World's End, I'd call it. I was finally ready to get started!

Which is when I realised that I knew absolutely nothing about the Edwardians.

The issue is that they don't seem to have their own identity - a seismic shift that still resonates today: by comparison, the Victorian era has heaps of personality, with leaps in science and technology, people exploring the world and deciding to steal most of it, stovepipe hats, penny farthing bicycles, fun facial hair... I could go on.

The global success of Julian Fellowes' Downton Abbey has definitely helped to change that a little, but I wouldn't be surprised if a lot of people, when questioned, misremember that first series as being set in the Victorian period.

As a result, I approached my research with a sense of dutiful, grudging boredom - a bit like being forced to learn about Roman aqueducts in school. I'd wanted to write a fun, thrilling murder mystery caper... was I really going to have to wade through hundreds of pages of bone-dry material, just to make that happen? "Why couldn't the Halley's Comet Panic have happened 40 years earlier," I hissed through gritted teeth, "so my detectives could ride steam-powered penny farthings to the murder site or something?"

But what I discovered - and what I suspect might be true for a lot of other people - was that I was massively wrong about the Edwardian era.

Maybe the key element at play is the one I've already touched on: it wasn't the Victorian period. Britain had just experienced several decades of incredible, dizzying boom, expanding its colonies and becoming the most powerful Empire in the world. Now, all that had stalled: in the eyes of the nation, Queen Victoria had died, a golden era had passed, and Britain didn't feel like the powerhouse that it once was. There was a paranoia that things were falling apart: that somehow, for some reason, we were at threat, and nobody knew why.

Perhaps part of the reason was how much everything was changing. There were demands to improve society at a fundamental level: for greater equality, for the vote to be extended to all men and all women, for the huge wealth that the country had amassed over the previous decades to be better shared among its people.

There was a constant sense of impending war across Europe, and a pervading xenophobic threat of outsiders. People were convinced that German spies were infiltrating the country, that Chinese immigrants were stealing our women and getting our children addicted to opium.

Most importantly, no one seemed to agree on anything. There were hung parliaments, bitter divisions over huge issues. People saw the demands for better social equality and universal suffrage as symptoms of some greater illness: that the fabric of society was being altered, and that was why nothing felt right anymore.

Everyone was unsure, tetchy, paranoid. People seemed to know that something terrible was about to happen... and of course, it was. The world was hurtling headlong towards war: it was like everyone could see it coming, and they panicked about it, right up until the point it did. During the first Balkan War, Winston Churchill described the terror that lay ahead if war in Europe wasn't prevented: "The only epitaph which history could write upon such a catastrophe would be, 'This whole generation of men went mad and tore themselves to pieces'."

Frankly, the more that I read about the Edwardian era, the more it reminded me of now. As a country, we're obsessed with our past: with an unspecified golden era, a sense that Britain used to be good, but now it's dreadful and something has to be done about that.

No one actually agrees on what used to be good, and what is now bad: in fact, arguing with each other seems to have become the background noise of the last ten years. I've never known a period of time where two people are less likely to agree on something. The news is a constant ticker tape of demands for better human rights, a paranoia that the threads of society are being unravelled, a growing sense of panic that the world is gearing itself up for war... no wonder we've started putting flags on roundabouts.

Which is maybe why writing a murder mystery in the first place felt so appealing to me - and why cosy crime is experiencing a year-after-year boom in the publishing industry. The world feels like a pretty scary place at the moment, and murder mysteries, even the straight-faced ones, are fun.

Real life is baggy and confusing and doesn't make sense most of the time. By comparison, murder mysteries are intricate little puzzle boxes that are completely self-contained, always solvable, satisfying to read because every single possible thread is covered within its pages, nothing left out. If you read a murder mystery and the conclusion was that the victim was killed by a complete stranger who had absolutely no motive, you'd fling it across the room in disgust.

The Murder at World's End doesn't do that. It's got secret passages and locked rooms and family secrets and red herrings and a central pair who start off at each other's throats but then work together perfectly at the end. They catch the killer and reveal the truth and then go on to solve a series of further mysteries. And hopefully, I give people an insight into the Edwardian era too, and why it deserves our attention now more than ever.

But you'll be thrilled to know that I got rid of the sex scene, because it really was absolutely terrible.

- The Murder at World's End by Ross Montgomery (Viking, hardback £16.99) is out on Thursday (OCT 30).

You may also like

Brits told to sprinkle cayenne pepper in their home in November

Tom Aspinall's huge net worth, very private wife and retirement plans ahead of UFC 321

Indian Ambassador to US extends Diwali greetings to citizens, diaspora (IANS Exclusive)

Prince Archie and Princess Lilibet could make UK appearance for major event

Strictly Come Dancing's Vicky Pattison breaks down in tears as fans left raging